ARTstor just released a

new interface--probably in beta. I think it does away with the Java in favor of modern AJAX techniques, a good move. ARTstor and, more generally, the provision of images of art and cultural objects to academic populations is a good example of how things are moving to the network level.

Visual Resources is one of my areas of responsibility here at Watzek, and its interesting how much faster things are moving in this area than in "mainstream" library collections. The continued viability of the monograph has kept the pace of going digital relatively moderate in library stacks.

With our College slide collection, however, we've seen our users (mainly Art faculty) almost totally abandon slides over the course of five years. It would be quite a shocker if library stacks fell into disuse at that pace especially because there is so much organizational and physical infrastructure surrounding them.

When Margo, the Visual Resources Curator, and I approached the problem of "going digital" in visual resources back four years ago, the route we choose was to build an institutional collection of digital images using

MDID. The images would be a combination of images scanned for faculty and purchased high quality digital images. MDID software is designed to provide a comprehensive environment for teaching with digital images. It stores an institutional collection of digital images, has a space for personal images, and a suite of presentation tools geared towards teaching Art or Art History. Our vision was that MDID would be the central place to find and work with digital images for teaching.

Though

MDID@LC has grown and faculty use it to find high quality stuff, things haven't quite turned out as intended. Faculty, especially the ones that are confident technologically, have their own tools that they know and like to use for presentation, chief among them, Powerpoint. They also like to maintain their own collections of images on their own computers. (It would be nice to nudge them along to networked software for their personal images like Flickr, but that's another topic).

Except for the faculty that follow our guidance directly (those that tend to be the least confident technologically) most folks don't use MDID to present. It's just another silo that they check when they are looking for images, along with ARTstor and the web. This is leading us to the conclusion that in the interest of breaking down silos, we should mount all of our institution specific images in ARTstor.

Fortunately, ARTstor offers a hosted collection feature which does just that, albeit with a few limitations. In the past, when libraries purchased collections of digital images, they had to host them themselves in their own digital asset management systems. Now, when we want to license a set of images from a company like

Archivision, they just "flip a switch" and the collection shows up in our ARTstor account. We can also upload our own collection of images into ARTstor at certain intervals (which will need to be increased to really use ARTstor to provide our image services to faculty).

ARTstor is a great example of the advantages of "moving to the network level." It's platform that's being continually improved and a collection of resources that's being constantly expanded. One of the cool things about it is that it groups together different images of the same work of art--sort of a FRBRization of images.

Our experience with both ARTstor and MDID really shows that building isolated, institution focused collections just doesn't make sense. In this networked world, our local assets need to co-mingle with those on the network and become part of that greater whole. I suppose this is also the idea with the WorldCat.org platform and its various permutations. To invest heavily in our local library catalog database and its search platform bears some similarity to investing in MDID.

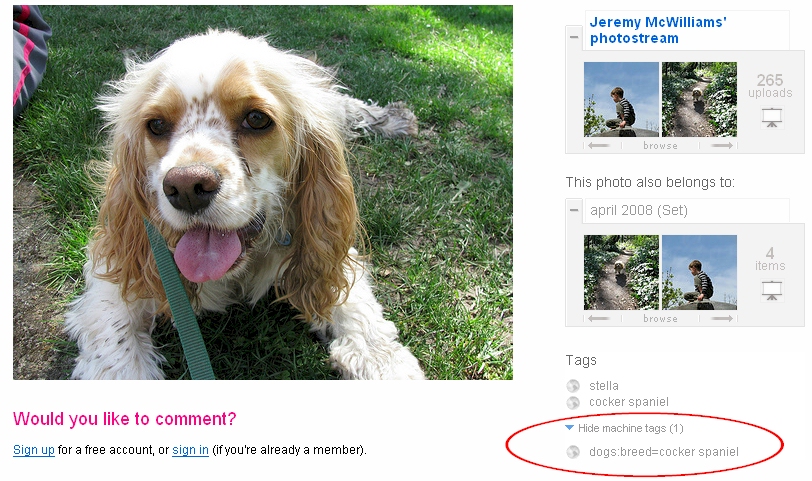

Now, I'm not saying ARTstor couldn't go further. I've always thought that they should "mobilize" their content by syndicating thumbnails of their content in search engines. And then there's the matter of the

academic Flickr.